An Uncatalogued Asteroid Could Kill Hundreds of Thousands Tomorrow. Why Aren’t We Prepared?

What will it cost to do something about it right now?

“This hazard exists because our planet orbits the Sun amidst millions of smaller objects that cross Earth’s orbit, including asteroids and comets. Even a rare interstellar asteroid or comet from outside our Solar System can enter Earth’s neighborhood.”

-

The 2023 Planetary Defense Strategy and Action Plan

Warning Shot

The explosion on that frigid Friday morning released more than 30 times the energy of the Hiroshima atomic bomb, scientists would later calculate.

It was just after 9:00 a.m. on February 15, 2013, when the Russian city of Chelyabinsk looked skyward and saw the sun replaced by an impossible fireball. Some residents could even feel its heat on their faces. Moments later, the meteor exploded over the city.

The explosion sent a powerful shockwave that shattered thousands of windows. Scientists estimate the space rock was about 20 meters or sixty feet – the size of a six-story building. It was traveling at an incredible 68,000 kilometers per hour. Although most of its energy was absorbed by the atmosphere, the blast was still forceful enough to send 1600 people to the hospital and cause the earth to shake a hundred kilometers away. The shallow entry angle of the meteor, which caused it to break apart high in the atmosphere, likely saved the city from much more severe damage.

How much warning did the citizens of Chelyabinsk get? None.

The asteroid1 caught us unaware. If it had been slightly larger or had struck at a steeper angle, the consequences of our obliviousness could have been far worse.

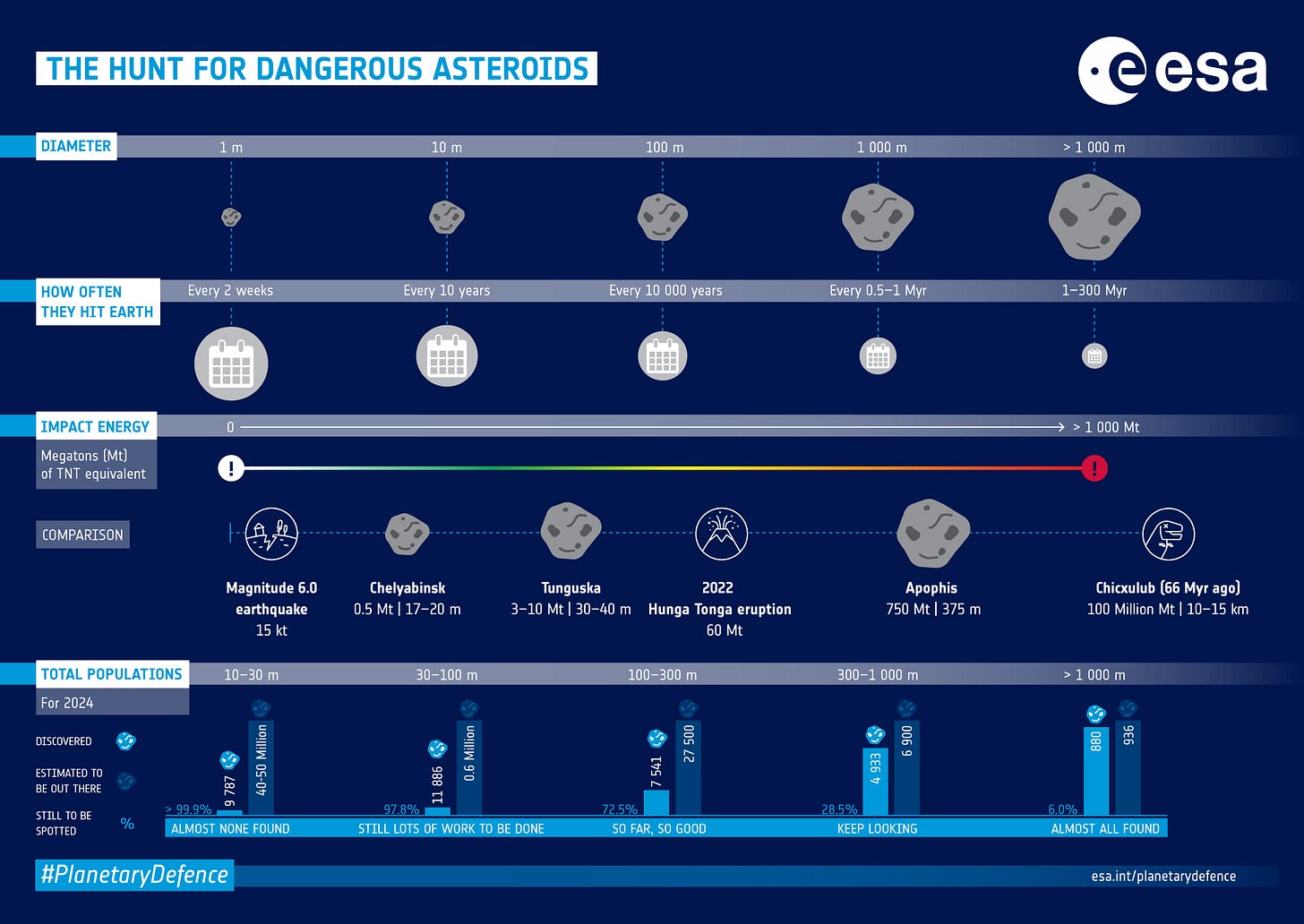

The uncomfortable truth is that we are best prepared for the least likely case: more than 95% of the bigger, rarer asteroids (civilization-enders, greater than 1 km in size) have been catalogued. And although that is an incredible achievement, it still leaves us ill-prepared for the more likely case: the “city-killers” and “regional-killers” in the size range of 50 to 200 meters. A 2025 NASA-run hypothetical simulation of an asteroid impact scenario estimated a death toll in the hundreds of thousands for an asteroid 140–160 m (460–520 ft) in size. Currently, NASA says, we track only half of the asteroids larger than 140 meters in size, and less than ten percent of the asteroids larger than 50 meters in size. This means that there are more than 200,000 asteroids larger than 50 meters that we currently do not track2. Statistically speaking, at least one of these hidden asteroids is already on a collision course with Earth – we are just unaware which one, and when.

So, although there are millions of asteroids (the majority of which circulate between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter), the ones that we have to worry about are classified under Near Earth Objects, or NEOs3. NASA updates this dashboard of Near-Earth Asteroids monthly, collating data from comprehensive, continuous observation efforts that include ground-based telescopes, orbital assets, and other impact risk assessment systems. The current count of detected near-Earth asteroids is approximately 39,000 (as of September 2025). And in the past year alone, at least one of these asteroids has passed by us closer than the moon every two days.

A 2025 analysis estimates that a city-killer asteroid strikes Earth approximately once every 11,000 years. This translates to a small 0.009% chance per year. To dismiss it as “low odds” is the kind of intellectual laziness we cannot afford. The true measure of risk is simple: multiply that “small” annual chance by the catastrophic cost – the complete destruction of a major metropolitan area. We already think like this for other threats with similar risk arithmetic. We currently budget billions to reinforce structures against the Cascadia Subduction Zone4, a low-probability terrestrial threat we cannot prevent. And we have already spent billions of dollars to make aeroplanes so safe that, in a given year, you are a thousand times less likely to die in an air disaster than the earth’s chances of getting hit by a city-killer asteroid. A similarly serious plan would treat the once-every-11000-years (i.e., a 0.009% chance) of catastrophe as a severe, practical problem. The failure to apply that same practical logic to the preventable asteroid risk is indefensible.

We would be wise to consider Chelyabinsk not as an anomaly but a warning shot.

No Two Ways

Professor Matthew Stanley, a historian and philosopher of science at NYU, contends that an asteroid collision scenario can be viewed as a scientific, secular, modern parallel to the end-of-the-world scenarios of a quaint, more religious, bygone era — and like religious matters, there are schisms to be found here, too5.

The schism of interest to us began immediately after the Cold War ended in the early 1990s. One side favored better eyes in the sky to track dangerous asteroids but warned against the weaponization of space. Led by the astronomer and public intellectual Carl Sagan, this side argued that the balance of risk is against developing space weapons. Because the asteroids are rare, they argued, any such weapons are more likely to be used by humans against other humans while we wait for a celestial threat to materialize. When you have a hammer, the thinking went, other people might appear as nails. Hence, Sagan and co argued, it is better to develop capabilities to detect a potentially hazardous asteroid decades in advance and then, once detected, develop combative technologies to deal with it.

The other side, led by ‘the father of the Hydrogen Bomb’ Edward Teller (who cut his teeth at the Manhattan Project), wanted investments in kinetic planetary defense methods – including and up to nuclear weapons. They argued that by the time we spot an asteroid on a collision course, it might already be too late.

A generation later, Sagan’s thinking has clearly prevailed. We catalogue asteroids with increasing sophistication (but nowhere near absolute certainty), and can track them as they move around in our celestial vicinity. However, all methods of intentionally perturbing their movement for our eventual benefit remain in the realm of theory – with one remarkable recent exception in the form of DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test), launched by NASA in 2021. Even NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO), which was established in 2016, has its mandate as “finding, tracking, and better understanding asteroids and comets that could pose an impact hazard to Earth” – notice the complete lack of any hint at “mitigation” here.

Although it would be easy to dismiss Edward Teller and co as weapons scientists finding ways to remain employed after the end of the Cold War, I am not so convinced. The seriousness of the asteroid threat warrants a multi-pronged approach. Detection, deflection, and destruction must all be considered as valid mitigation efforts. Yet not all are equally practical today. I will focus on the first two – detection and deflection – in the Rapid Planetary Defense Program (RPDP) outlined below, as these are achievable with modest investments in time and money. Destruction is energy-intensive and will most certainly require nuclear weapons in space – and these are banned by international agreement since 1967. Nuclear standoff detonation is also the most effective way to deflect an asteroid in an emergency. My only suggestion for now would be to carve out a planetary defense exception to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

Detection: Deep and Wide

When it comes to gazing into space, the technological eyes of our telescopes face the same tradeoffs as our biological eyes gazing into the night sky. A quick, wide scan sacrifices depth to encompass the entire sky. A focused look into the dark depths, on the other hand, takes time and takes in a narrower slice of the sky. So, “width” means you spot asteroids across a bigger portion of the sky, but they are nearer when you first see them. And “depth” means you can track an asteroid from farther out, but only in a specific section of the sky at a time. The superstars of space telescopes, the Hubble and the JWST, are of the latter kind. They have a very narrow field of view, meant to single-mindedly observe the celestial slice of interest to scientists at the moment, and are not meant to scan for asteroids. To scan for asteroids, you need a patchwork of eyes to cover as much of “width” with as much of “depth” as possible.

Until very recently, as recently as June 2025, the heavy lifting in asteroid detection was done by a handful of ground-based surveys, such as Pan-STARRS in Hawai‘i, Catalina in Arizona, and ATLAS, which has a global network of two small telescopes (two more are planned). Their focus has been on the larger bodies (those 140 meters across and larger, the city/region-killers) that could level a region or devastate a coastline (an asteroid falling into the ocean can cause a tsunami). But if they are the first to spot a city-killer, it may already be too late. The ATLAS website says, “ATLAS will see a small (~20 meter) asteroid several days out, and a 100 meter asteroid several weeks out.” We don’t yet have the technological wherewithal to deal with a 100-meter asteroid in several months, let alone “several weeks”6. And given that more than half of the asteroids of this size (and bigger) are uncatalogued, that’s a real problem. Maybe that’s the reason why ATLAS stands for Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System.

2025 has brought a revolution in ground-based observations: the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. It’s a revolution because, for the first time, the tradeoff between width and depth did not feel so stark. Equipped with a mammoth 8.4-meter telescope and the world’s largest 3,200-megapixel camera, it scans the Southern sky from a mountaintop in Chile, once every three nights7. Within months of first light, Rubin had already added thousands of new asteroids to the tally. Over the coming decade, it is expected to triple the known inventory of potentially hazardous objects, mapping over 127,000 near-Earth asteroids and millions of smaller bodies. Its wide-field cameras and lightning-fast re-imaging capabilities let astronomers track faint, fast-moving objects with a clarity that was once impossible. More importantly, for the first time, color data and repeated passes give scientists an early glimpse into the composition and behavior of these objects (not just their orbits). This is the kind of data we will need when (not if) we need to deal with an asteroid on a collision course with Earth.

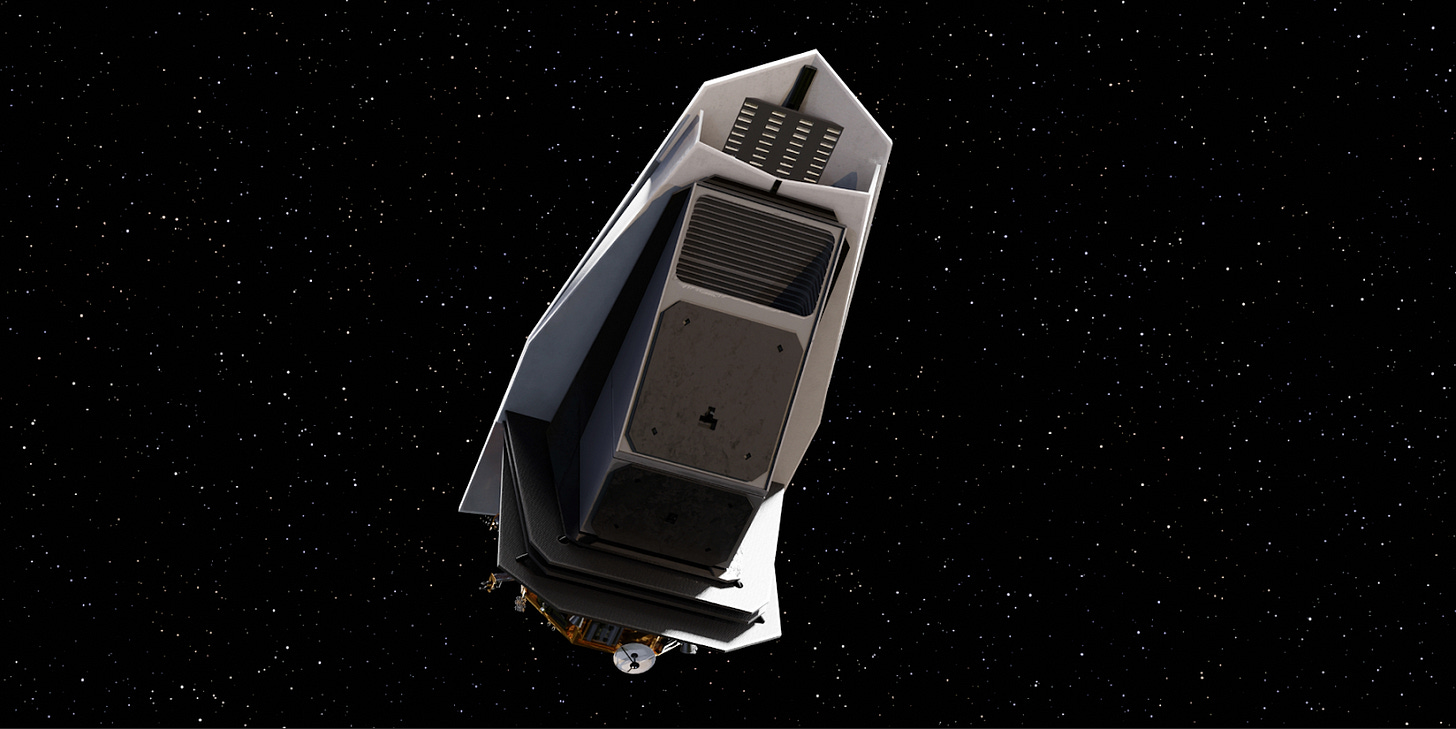

However, all ground-based observations suffer from some limitations: they can only cover half the sky at most, so you need multiple telescopes communicating with each other. And they are at the mercy of local weather and limited by interference from Earth’s atmosphere. They are also helpless against asteroids hiding in the sun’s glare. That’s why NASA’s proposed NEO Surveyor, which is supposed to be launched in 2027, is so important. It will scan the skies in the infrared, and hence will be able to spot the dark, heat-soaking asteroids invisible to optical telescopes on Earth. Crucially, from its vantage Lagrange-point8 in space, it can also see objects hiding in the glare of the Sun – the blind spot of ground-based telescopes. Its goal is ambitious: to identify two-thirds of the unknown asteroids larger than 140 meters within just five years. Fully funding and launching the NEO Surveyor is the single most impactful step we can take. Yet, the future of this mission is uncertain in the proposed FY 2026 budget (which includes a 24% cut to NASA’s total funding and a 32% cut to its Planetary Science division)9.

The ground-based and space telescopes must also be able to pool their time-sensitive and potentially life-saving data. To avoid the “blind men and an elephant” problem, the International Asteroid Warning Network has expanded, linking observatories and space agencies through real-time data exchanges. Powerful new algorithms sift through nightly images, connecting faint points of light into coherent orbital tracks. When objects look suspicious, radar facilities step in to lock down size, shape, and trajectory with uncanny precision. Still, there are only so many radar dishes, only so many telescope nights to spare. Sudden floods of new detections can overwhelm capacity, leaving some objects in limbo until more resources free up.

Ground and space surveys must be capable of feeding real-time discoveries into automated tracking pipelines. Follow-up capacity needs to grow, including more robotic telescopes and additional radar time reserved for planetary defense. Launching and maintaining advanced space telescopes like NEO Surveyor is non-negotiable if the hidden population of dark asteroids is to be brought into the open.

So, detection is the first pillar of RPDP.

Let’s say the NEO Surveyor launches, let’s say we get a few more Rubin-class telescopes, and let’s say the fully-expanded International Asteroid Warning Network detects an asteroid a few years out on a collision course with Earth. What next?

Deflection: Need for a Civilizational Arsenal

The only space-proven tech we have for deflecting an asteroid is DART, or Double Asteroid Redirection Test. A mission launched by NASA in 2021, DART targeted a binary asteroid system some thirty Earth-moon distances away. It slowed the orbital period of the smaller asteroid by 33 minutes, providing proof of concept that asteroids can be deflected10.

DART took years to plan, and although we now have the science, we have precisely zero deflectors in storage. This is not good. Having an arsenal of deflection spacecraft ready – let’s call it the Hot Impactor Reserve – is the difference between spotting a charging gorilla with a hunting permit in hand and spotting it with a hunting rifle in hand. Hence, the second RPDP pillar must be the readiness to deploy deflection technology immediately following a detection event.

Currently, we have a “we’ll-cross-the-bridge-when-we-get-there” strategy when it comes to deflecting asteroids. However, such a strategy only works when there’s an actual bridge already there to cross. We are currently without a bridge on the wrong side of the abyss. That is to say, we need a shelf-ready fleet of kinetic impactor spacecraft, inspired by NASA’s successful DART mission. These need to be robust, modular, and purpose-built, with standardized components and commercial avionics. These must be designed to be stored, maintained, and prepared for lightning-fast integration with available launch vehicles. We cannot wait until we are forewarned to be forearmed: a new design-and-build cycle for a fleet of DARTs will take at least half a decade (and that’s an optimistic estimate).

Having the Hot Impactor Reserve allows for a response within a two-year timeframe. All we have to do then is pull a spacecraft from storage, run final checks, integrate with a rocket, and launch11. The result: credible defense and the ability to deflect a threat before time runs out, enabled by on-call hardware12.

However, no amount of hardware can protect the Earth if it is mired in bureaucratic delay.

To implement RPDP, we also need a well-oiled governance machinery with the ability to mobilize scientific, technological, and logistical resources worldwide. Logically, it should be NASA’s PDCO (Planetary Defense Coordination Office), but with an expanded mandate that includes mitigation efforts. Ideally, the PDCO must be empowered to coordinate across civil, military, emergency, and diplomatic lines. It should also have its own direct budget authority. Planetary defense is too essential to compete for scraps in a sprawling science portfolio. It should stand on its own as a dedicated pillar in the national security infrastructure – because that’s what it is.

Asteroids are natural, non-adversarial threats, but they are planet-wide threats nonetheless. Nations need to treat asteroid defense as shared infrastructure. While the hardware presents an engineering challenge, and its implementation a logistical one, the geopolitics of deploying it will present a profound test of global governance. The possibility of an imperfect deflection that just shifts the impact corridor from one continent to another can make things complicated, to say the least.

Sagan’s objection13 that “if you can deflect an object away from collision with the Earth, you can also deflect an object not on collision trajectory so it does collide with the Earth” is valid. The authority to alter a celestial trajectory is a grave responsibility that must be shared, and the mutual trust cannot be improvised under duress. This is why a pre-negotiated international framework for decision-making is an absolute requirement. The asteroid must not find us in disarray. A planet divided cannot prevail.

Practically, preparedness will include regular, full-scale operational exercises. We must utilize real near-Earth objects as test cases to practice discovery, tracking, decision notification, and the actual rollout of spacecraft. These exercises will foster trust, refine procedures, and ensure that agencies (such as NASA, DoD, FEMA, etc.) and nations are prepared to work together as a team under time pressure. The success metrics may include, for example, a detection-to-certainty time of under 30 days, a decision-to-launch time of under 18 months, and a system availability of above 95%, among others. These exercises simulating impact scenarios would build trust, coordination, and the kind of muscle memory that can save time when time matters most. This is how we transform RPDP from theory to a reliable capability.

It’s a Bargain, Not a Moonshot

So the good news is that building the Rapid Planetary Defense Program, with all its speed and readiness, is not science fiction. And here’s another good news: it is not a financial fantasy either. In defense spending, everything is relative. A single B-21 bomber runs more than $700 million. A Gerald R. Ford–class aircraft carrier tops $13 billion. Even a modest missile defense upgrade costs several billion dollars per year. Against that backdrop, the numbers say that a Rapid Planetary Defense Program is a bargain.

Imagine the world’s finest detection system: NASA’s upcoming NEO Surveyor, our infrared sentinel in space, reinforced by a younger sibling early next decade. These get ground support from another pair of rapid-fire digital eyes inspired by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Together, for NEO Surveyor and a slice of the Rubin investment, their price tags today total less than $2 billion, including modest annual operational expenses.

Programs like ATLAS add vital global coverage at just a few million dollars per site. On the ground, a dedicated program office, smarter data pipelines, and radar time reservation bring the annual running budget to a fraction of what we spend on weather satellites or a single new stealth bomber.

And what about the Hot Impactor Reserve? The DART mission, which proved that a spacecraft could nudge an asteroid, cost approximately $325 million. Now, imagine building a small, standardized, ready-to-go fleet. It could save continents. The price? Around a couple of billion dollars more, but spread over a decade, leveraging mass production and streamlined engineering.

And because this is not just another research project that might never see the outside of a scientific journal, but a standing capability that might one day mitigate an existential hazard, it can be structured as a true public works program. Just as highways, dams, and power grids seeded industries and jobs for generations, so too would a planetary defense build-out. Aerospace suppliers, robotics firms, optics manufacturers, software companies, launch providers – all benefit. Universities train the talent, the spending vitalizes local economies, and the nation gains a defense against catastrophe, while setting up an economic engine with spillover effects across sectors.

When you total it up, the entire RPDP (with advanced surveys, a fleet of kinetic deflectors, radar assets, and a single, unified governance structure) requires a $2–4 billion up-front investment, and $200–300 million yearly to operate and exercise. This includes the ongoing costs for operational drills, readiness exercises, and governance. That’s less than the cost of maintaining a fleet of fighter jets for a single year, and a tiny, really tiny, fraction of the annual U.S. defense budget.

Think of it as a prudent planetary insurance policy: as a way to turn world-class science, proven engineering, and focused funding into quiet, dependable readiness. By some literal cosmic good fortune, this celestial problem didn’t appear when we were conceptually blind and technologically hopeless. We are no longer conceptually blind, yet we remain woefully unprepared technologically. This puts us in an indefensible position, literally and metaphorically. We don’t get to choose when an asteroid will appear on the celestial horizon; we only know that one day it will. But we do get to choose whether we are ready for it.

The proposed Washington Commanders’ NFL stadium is slated to cost around $4 billion14. In other words, for the price of a city’s stadium, we could safeguard Earth from a catastrophe that threatens everything we hold dear. And the time to invest in our planetary safety, to buy that insurance before disaster strikes, is now. The question is no longer “Can we afford to do this?” but “How can we possibly justify not doing this?”

I am grateful to Mike Riggs for his editing and encouragement and to Emma McAleavy for her insights into the writing process. I thank Steven Adler, Byron Cohen, Sarahi Enriquez, Lesley Gao, Adam Kroetsch, Hiya Jain, Ariel Patton, Karthik Tadepalli, Deric Tilson, Elizabeth Van Nostrand, and Kelly Vedi for feedback and discussion during the drafting phase. Special thanks to Professor Matthew Stanley for his insights into the intellectual history of the asteroid threat and to Hiya Jain for making the introduction.

Asteroids are large, orbiting space rocks. A meteor is the fiery streak of light you see when that fragment enters the atmosphere (a “shooting star”); and a meteorite is the piece that survives the friction and actually impacts the ground.

National Science and Technology Council, National Preparedness Strategy and Action Plan for Near-Earth Object Hazards and Planetary Defense, 2023, accessed September 27, 2025, https://assets.science.nasa.gov/content/dam/science/psd/planetary-science-division/2025/2023-NSTC-National-Preparedness-Strategy-and-Action-Plan-for-Near-Earth-Object-Hazards-and-Planetary-Defense.pdf

The Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) is a 680-mile-long, locked tectonic boundary off the Pacific Northwest coast, critically capable of triggering a Magnitude 9+ megathrust earthquake and subsequent tsunami that will devastate the region.

Dr. Matthew Stanley, personal communication with the author, September 23, 2025.

Astrum, “First Ever Images from the Vera Rubin Telescope,” YouTube.

A Lagrange point (L-point) is a position in space where the gravitational forces of two bodies create a stable gravitational balance. There are five such points (L1 through L5) for the Earth-Sun pair. The NEO surveyor will be parked at L1, giving it an unobstructed view into the Sun’s glare to find hidden asteroids.

Inflation-adjusted, the proposed 2026 NASA budget is lower than it was in 1961.

A follow-up mission launched by the European Space Agency, Hera, will provide more details about DART’s impact when it reaches the binary asteroid system in December 2026. Meanwhile, the data from the DART mission is still being analyzed, and new findings continue to be reported. For example, see “We Just Broke An Asteroid In Half”: NASA Reveals Space Rock Turned Into Rugby Ball Shape

The fact that the “launch” part of this plan is the only currently ready and reliable part is primarily thanks to SpaceX; its commercial investment has delivered the reliability and rapid cadence that an asteroid-deflection program will critically need.

While a “Hot Impactor Reserve” of kinetic impactors represents the only space-proven and most pragmatic first line of defense, a truly robust planetary defense strategy must be multi-layered, with an arsenal of tools suited for different threats. This reserve forms the essential first tier: reliable, ready, and effective for the most probable scenarios. Backing this up, we must continue to develop other technologies, such as the precision, long-lead-time force of a gravity tractor, the ablative thrust from focused energy beams (e.g., lasers), and, for catastrophic short-notice threats, nuclear standoff detonation. See https://www.nasa.gov/solar-system/did-you-know/

Carl Sagan, “Between Enemies,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 48 (May 1992): 24–26. (Look, I love Carl Sagan as much as the next guy, owe my obsession with space to him, but I think he got the balance-of-risk wrong in this case. Maybe he’d appear more sensible to me if I had lived my life through the constant fear of nuclear annihilation during the Cold War and did nuclear bomb safety drills as a kid. But humanity survived the Cold War (thanks in part to Sagan’s public outreach on how horrible a nuclear war would really be) — and the balance of risk has changed now. We didn’t come this far only to come this far.)

We need an international space force. I’m surprised at how comparatively inexpensive this would be.

Mother nature is much bigger than humankind, there are so many such things that we ought to pay attention to, but are we obsessed with man-made afflictions which pale in comparison...