Explanations Are Forever

Two Taxi Drivers, One Space Agency, and the Only Case for Fundamental Science.

Demon-Haunted, Still

I arrived at the Progress Conference on the evening of October 15th after five hours of flying and one ninety-minute Uber ride from SFO to Berkeley—during which the conversation with the driver drifted far outside the realm of peer-reviewed reality. This, dear reader, was not how I had imagined my Carl Sagan moment. Sagan, in Demon-Haunted World, tells us an anecdote of his conversation with a taxi driver who said he wanted to talk about science but bombarded Sagan with conspiracy theories:

“And so we got to talking. But not, as it turned out, about science. He wanted to talk about frozen extraterrestrials languishing in an Air Force base near San Antonio, ‘channelling’ (a way to hear what’s on the minds of dead people - not much, it turns out), crystals, the prophecies of Nostradamus, astrology, the shroud of Turin .. . He introduced each portentous subject with buoyant enthusiasm. Each time I had to disappoint him:

‘The evidence is crummy,’ I kept saying. ‘There’s a much simpler explanation.’ ”

My Carl Sagan moment wasn’t much different. When my driver found out I’m a scientist, he started asking me questions about the comet 3I/ATLAS. Well, these were more comments than questions. He was sure the comet was an alien ship and that the aliens onboard, when they get here, will speak Arabic and confirm that god exists. I replied that the comet was interstellar, and since even the light from the nearest star takes about four years to reach us, any aliens on the ship must be capable of surviving a few thousand years. He rejected my ‘claim’ that light from the nearest star takes years to reach us, and asked me what else scientists know about the comet. I told him that because of the government shutdown, NASA hasn’t been able to study the comet properly. “Do you think it’s a coincidence?” — he asked rhetorically. He just knew it was a cover-up…1

The conversation did get me thinking about how to make the case for fundamental research to the public that funds it (and this includes the taxes the Uber driver pays). This was one of the things that was on my mind during the Progress Conference2 — for two reasons. First, the Conference was attended by people who seemed sure of the “Why” of what they were doing, and were debating the “How” and “What” questions. Second, right on the heels of the Progress Conference, I was going to the NASA Missions Ideation Factory (NMIF) on Astrobiology. The focus of this year’s NMIF—scheduled for October 19-24 in Cleveland, Ohio—was on developing mission concepts for the search for life in “Ocean Worlds” in our solar system. How do I explain the “Why” of that research?

All These Worlds Could Be Ours

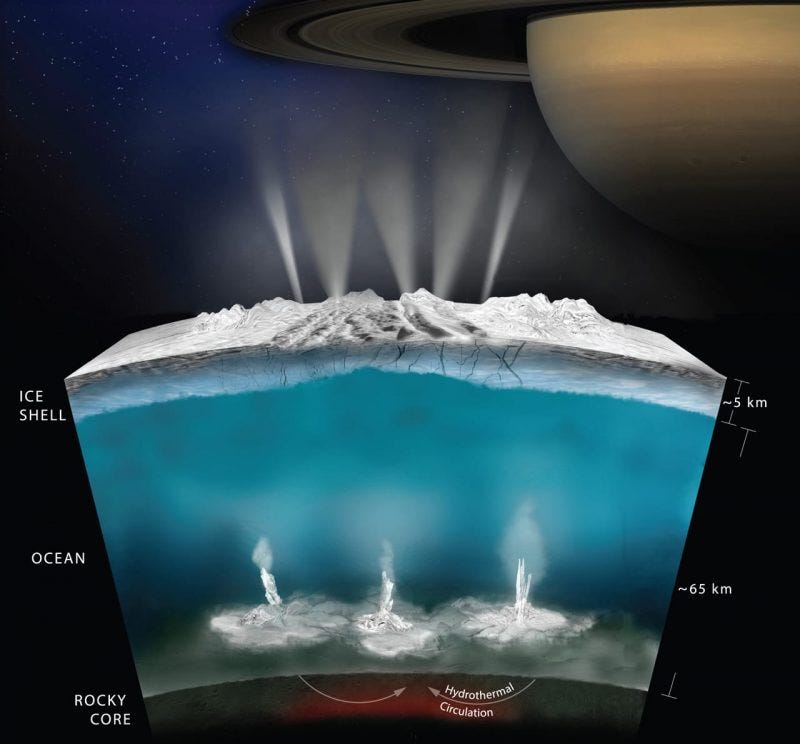

Earth is not the only world in the solar system with liquid water. Not just that, of all the worlds in the solar system with liquid water, Earth ranks near the bottom. Multiple icy moons—most notably Europa, Ganymede, Callisto (Jupiter’s moons), Titan and Enceladus (Saturn’s), and possibly others—are believed to have vast subsurface oceans of liquid water beneath their icy crusts.3 If we find life on Ocean Worlds, there’s a high chance that it will be extant life, and not just extinct fossils. The presence of liquid water makes Ocean Worlds tantalizing targets for life-detection missions.

Tantalizing— and challenging.

The first challenge is that these ocean worlds, which orbit the outer planets in the solar system, are really far away. Jupiter, the nearest outer planet, is ten times farther away than Mars is from Earth. Getting to these ocean worlds will take the better part of a decade, at the very least. So all the science we want to do, we have to do on site; taking samples and bringing them back to Earth for analysis is impractical with current propulsion technology.4

The second challenge is getting to the water. Earth may have a comparatively small amount of liquid water in the solar system, but most of that is on the surface. In the ocean worlds, liquid water is beneath thick shells of ice. And the thickness is estimated to range from a few kilometers to a few hundred kilometers.

I became fascinated with ocean worlds when, during my PhD, I read The Mission by David W. Brown about the Europa Clipper mission, which is currently en route to the Jupiter system.5 Europa Clipper took multiple iterations through three decades to realize—an entire generation’s work. This process and duration will be typical of Ocean World missions for several reasons.

Firstly, as already mentioned, they are far away.

Secondly, the orbits aren’t always ideally aligned. So, unlike Mars, where a launch window opens every 26 months or so, energy-efficient trajectories to the outer solar system often require specific planetary alignments (for gravity assists) that can be much rarer and fleeting.

Thirdly, as always, are the cost considerations over these long planning phases. Governments and their priorities change, and funding gets canceled or reallocated to more promising targets. (This was especially salient given the then-ongoing government shutdown, which had forced a last-minute change in the Ideation Factory venue from NASA Glenn Research Center to Hotel Indigo Cleveland Downtown.)

Given all these reasons, it’s a miracle that these missions fly — and not just a technological one. Not only do planets have to align (literally), but stars, too (metaphorically). This was impressed upon us early-career scientists by the veteran NASA mentors at NMIF. Some of them even joked that they might be long dead before the missions being conceptualized during the week reach their targets.

In What Furnace Was Thy Brain?

NASA Mission Ideation Factories are, as the website explains, “intensive and interactive workshops focused on developing creative ideas for future life detection missions.” And boy, it was intensive.

The expectation for audacious ideas was set early on when one of the facilitators said, “It is easier to tame a tiger than make a murderous lamb.”

With that mindset, we spent the week covering the walls with progressively larger Post-it notes containing ideas for future missions. The ideas were based on prompts of HM (“How might…”), H2 (“How to…”), and—my favorite—WIBGI (“Wouldn’t it be great if…”). The aim was simple: work with every participant at least once to pick an idea, shape it into a mission plan under time pressure, and present it to the room. We were warned that by midweek we would need to choose one idea, form a team, and commit to it—and that Thursday would be the most demanding day of the week.

There was a lot of expertise—impressive people from all over the world6—supported by mentors from universities and research institutes across the US affiliated with NASA. We workshopped in teams, adding more complexity each day, with peer and mentor feedback after every presentation.

The week was a blur of exhaustion and exhilaration. By the final Friday morning presentation, each team’s mission concept had sharpened, expanded, and taken on a life of its own. After the final presentations and goodbyes on Friday afternoon, after the all-nighter that almost everyone pulled on Thursday night, with my mind too exhausted to think about the details of the space missions, it was the non-mission-critical conversations that stuck with me. We had discussed, among other things, what brought us to astrobiology.

The Infinite Reaches

Astrobiology is a relatively new field of study that aims to understand the universally applicable definition of the process we call ‘Life’, treating life on Earth as just one of the many possible instantiations of ‘Life’ in the Universe. But the field is working with a sample size of one. That is why finding life–preferably extant life–is the holy grail of astrobiology.

Any such field attracts dreamers. But realization requires resources. And pursuing fundamental questions—like whether jellyfish float in the subsurface oceans of Europa—rarely offers the profit margins demanded by private capital within acceptable timeframes.7 At the temporal and monetary scales required by fundamental research, funding resources must come from the government. Which means, they have to come from the public.

Why does a median person care about alien jellyfish? At the NMIF, we mostly defaulted to the utilitarian defense: how research into fundamental science has enabled downstream discoveries like MRI and other life-saving technologies, how the handheld drill was invented because the wired ones won’t work to fix a leak on the outside of the International Space Station. But none of us chose astrobiology for the power drills, of course. We made the choice to spend our one wild and precious life attempting to find life on other worlds because of, as Feynman put it, the pleasure of finding things out. And also because of–there’s no denying it– implacable curiosity.

But this curiosity has to be trained, or it can get out of hand—at least that’s what I believed, especially after my Carl Sagan moment on the taxi ride earlier in my trip.

I had flashbacks of that taxi ride on another taxi ride on the last day of my trip—in the final leg from El Paso International to my apartment in Las Cruces. But this conversation strengthened my faith in humanity.

My driver, Joel, was a native El Pasoan in his early twenties. He was full of curiosity—technically untrained curiosity, as he never got a chance to go to college. When Joel found out that I was a scientist interested in space-related research, he excitedly said he loves space and that he has a friend who has been to space. I was incredulous, but then I googled his friend “Rick C J”, and sure enough, he had been to space. Rick, or Frederick W. Sturckow, is a former NASA astronaut. Sturckow now works for Virgin Galactic. Joel met him when he drove Sturckow from El Paso to Las Cruces, the gateway to Spaceport America, where Virgin Galactic operates.

Joel also asked me if I had seen A Trip to Infinity, a documentary on the concept of infinity. We then discussed the implications of the Infinite Hotel Paradox. Then, after I told him that I was coming from NMIF, I asked him the question that had been lingering on my mind: why should the public fund Astrobiology missions and other fundamental research?

Joel started to give the utilitarian answer, then stopped midway. Then, after a few seconds of silence, he said, “Because once we figure something out, we know it forever.”

And that, dear reader, is the only correct answer.

Joel, a man who had never stepped foot in a university lecture hall, had intuitively grasped the central thesis of the physicist David Deutsch: explanations have infinite reach.8

What justified funding Maxwell’s research into electromagnetism? It certainly wasn’t the utility. Any utility—telegraphs, radios, television, internet—lay decades and centuries in the future. How do you justify Ramanujan’s mathematics while Ramanujan was doing it? Today, his Math has applications from quantum computation to black hole physics — these concepts didn’t exist when Ramanujan did.

But Joel’s logic holds: once Maxwell unlocked the explanation for electromagnetism, humanity possessed it forever. It was only a matter of time before others could refine and build on them to let you make Zoom calls and read this essay on a screen. Our present internet, our future quantum computers, and our understanding of black holes all rest on the work of scientists like Maxwell and Ramanujan, who were doing what we now call “fundamental” research.

Deep, fundamental knowledge is a universal resource. Progress is cumulative and unforeseeable; once an explanation is found, its reach reverberates through all future technology, science, and culture. But the structures of scientific funding obscure this truth. Worse: they don’t even acknowledge it.

The inability of brilliant scientists—who solve thorny “How” and “What” questions in their research—to come up with a “Why” is mainly a result of learned helplessness. Their graduate training “tends to over-index on feasibility,” and the funding mechanisms only back incremental advances.9 This stands in stark contrast to the energy I felt at the Progress Conference. There, the ‘Why’—human flourishing, solving stagnation, building the future—was the ubiquitous baseline. Because we agreed on the destination, we could obsess over the paths and vehicles.

In modern academia, there is no shared destination. Without a consensus on the ‘Why,’ the ‘How’ degrades into securing funding until the next funding cycle. There are no giant leaps on this bureaucratic treadmill of incrementalism.

This retreat to the treadmill is a disservice to the spirit of humanity. It leaves the painting of the big picture to sensationalists who think a comet has aliens in it who speak Earth languages. It deprives open-minded and curious people who watch documentaries on the concept of Infinity. It risks disenchantment and, in doing so, invites despair.

To the “Why should we fund Astrobiology?” question, there’s only one honest, ultimate, non-utilitarian answer: because understanding our place in the universe is intrinsically worthwhile.

Every breakthrough makes humanity permanently richer in ways we can never foresee. It adds a line to humanity’s ledger, a deposit of knowledge that will compound in value long after we are gone. Everything else we buy with public money rots. The roads we pave today will crack; the machinery we build will rust. But a good explanation is a permanent asset. It is the only thing we — you, me, taxi drivers — can leave our children that time cannot take away.

Thank you to Emma McAleavy and Abby ShalekBriski for encouraging me to write about these experiences. I am grateful to Andrew Miller for extensive feedback on the structural issues with the first draft, and to Benedict Springbett and Tina Marsh Dalton for the “kill-your-darlings” feedback session on the second draft. Finally, thanks to Hiya Jain, Sarahi Enriquez, and (again) Abby ShalekBriski for comments and encouragement on the final draft. This was a surprisingly thorny undertaking; I could not have cleared the thicket without them.

Our conversation recovered when it meandered to our shared love of Indian food — he recommended some Indian restaurants in the Berkeley area, and I ended up visiting one while I was there.

which I got to attend as an RPI-BBI fellow. Much has already been written about the Conference. BigThink has published an entire special issue dedicated to it. And I will point the reader to the Reflections on Progress Conference 2025, which contains links to many of the write-ups and quotes from attendee reviews—nearly all of them are superlatives. I will only add that all of them are still an understatement.

And while Earth has about 1.335 billion km³ of liquid water, Jupiter’s moon Europa is estimated to have about twice as much liquid water as all of Earth’s oceans combined. Titan, Ganymede, and others are believed to have even more. Ganymede may even have the largest ocean in the Solar System.

Nuclear propulsion, if and when the technology is allowed to mature, will change that game completely.

I listened to the audiobook twice when it came out in 2021, and I highly recommend it! I also read the dead-tree version before the Ideation Factory — it has extensive footnotes that the audiobook narration doesn’t.

A representative sample: one had spent a winter in Antarctica drilling through ice cores; another had worked on an oil rig in remote Siberia; another was part of the Dragonfly mission, designing an aircraft to fly on Saturn’s moon Titan; and another was analyzing samples returned from the asteroid Bennu.

Private capital doesn’t fund exploration with the intention of advancing knowledge. The intent is always commercial. Have you ever tried to pitch a 20-year project with zero revenue to a Venture Capitalist? The meeting is usually very short. The virtue of private capital is its impatience and profit-seeking. It funds prospecting, infrastructure, and services. Contrast Asteroid Mining with Ocean Worlds missions. For the former, the intent is profit, the product is platinum/gold/water, and the theoretical ROI is massive. For the latter, the intent is knowledge, the product is knowledge, and the theoretical ROI is knowledge. We must not confuse commercial intent with scientific utility.

This concept, central to Deutsch’s book The Beginning of Infinity, argues that improving explanatory theories is the core engine of human endeavor, leading to a potentially infinite expansion of knowledge and control over our world, constrained only by physics.

As this anonymous post from a top scientist laments, the extramural funding system of NIH—the largest public funder of biomedical research in the US—tends to favor safer, incremental projects over high-risk, transformative research due to its peer review and funding structures, prioritizing feasibility instead of possibly transformative science.