The Harm in Hate Speech Laws

Why “group libel” cannot justify a hate speech exception to the First Amendment.

1. The Only Good Indians

Whenever “Indians” is trending on the site formerly known as Twitter, I – an Indian immigrant to the US – just cannot stop myself from having a look. Like one’s tongue to a loose tooth, my thumb(cursor) will reach for the ‘trend’ and tap(click) on it. With a strange mixture of dread and anticipation and morbid curiosity, I will scroll down the ‘Top’ posts, sorted by engagement. And it is always as pleasant an experience as fondling a loose tooth with one’s tongue.

Going by the majority of “Top” posts, there seems to be an open season on Indians broadly and Indian-origin immigrants specifically.

Just a sample from the last few days (and these are by no means the worst of the lot): ”Literally every product that comes from these companies has become worse since indians took over.”(quoting a post mentioning the many US companies with Indian-origin CEOs, 5.8k likes), “Indians are not loyal, are scammers, and are destroying America and jobs for Americans through fraud. It’s time to end all Indian Visas and deport all Indians in the US.”(posted with a defaced Indian flag, 5.1k likes), “America does not need more visas for people from India. Perhaps no form of legal immigration has so displaced American workers as those from India. Enough already. We’re full. Let’s finally put our own people first.” (Charlie Kirk1, quoting a Laura Ingraham post on a possible trade deal with India, 40k likes).

It is not just internet influencers; it’s also the people in power with positions of responsibility, who should know better (in terms of actual data and policy intricacies). For example, the governor of Florida has chimed in recently, criticizing the H-1B visa program, of which Indian nationals are the largest recipients, by targeting Indians (“most of them are from one country, India, there's a cottage industry about how all those people make money off this system”) and accusing "Big Tech" of undercutting American workers. This sentiment has been echoed and amplified by others with a bully pulpit: the current vice-President has explicitly questioned the loyalties of Indian-origin CEOs in Silicon Valley and framed high-skilled immigration from India as a threat to the American middle class. In both instances, complex economic and immigration policies are reduced to a simplistic and hostile "Americans vs Indians" narrative.

Why am I mentioning all of this? Because when I say I understand Jeremy Waldron’s point in his book The Harm in Hate Speech that “hate speech” — alleged or professed — is something which violates a person’s dignity and assurance, I really do. I understand it viscerally, not just vicariously.

I also agree with his definitions of dignity (a person’s basic social standing as an equal member of society) and assurance (a person’s ability to go about their lives without facing hostility or exclusion). Waldron gives me the explicit vocabulary to describe how I feel when I read explicit online threats by random weirdos and veiled targeting by public figures and powerful officials directed at Indians.

However, while ensuring dignity and assurance for members of a society (irrespective of their group identity) are worthwhile social goals as Waldron defines them, these are too nebulous to be legal goals. In this essay, I will make the case that “group libel” is not a legally sound basis for hate speech laws.

2. “Offense”, “Hate”, and “Group Libel”

I chose to focus on Waldron’s book because it represents the most sophisticated and intellectually rigorous modern defense of hate speech regulations. Published in 2012, The Harm in Hate Speech is arguably the most significant contemporary text on the topic, and it has drawn extensive praise for its rigor and sharp criticism for its conclusions. Waldron explicitly seeks to provide the "best case" for these laws, moving beyond what he calls "knee-jerk, impulsive, and thoughtless" arguments to build a nuanced theory based on protecting civic dignity as a public good.

The book's primary influence has been to shift the intellectual justification for hate speech regulation away from preventing "offense" to preventing “hate” by applying standards of dignity and assurance. Waldron is credited with clearly defining the terms of debate even by his critics. He makes it clear that he wants to distinguish between “offensive” speech and “hate” speech. In the first chapter itself (‘Approaching Hate Speech’), he writes: “I accept the point, which many critics make, that offense is not something the law should seek to protect people against.” However, I believe that the machinery of the state, once empowered to regulate speech, is incapable of maintaining such a fine distinction.

In the rest of this essay, I will focus on the concept of “group libel” in chapter three (‘Why Call Hate Speech Group Libel?’), and will argue that it is legally incoherent, and can only make sense within a collectivist worldview, despite Waldron’s protestations to the contrary. “Group libel”, hence, cannot justify hate speech laws.

3. The False Consciousness of Group Libel

The concept of libel refers to a defamatory statement that, unlike spoken slander, is committed to a more permanent form, such as "by writing, printing, effigy, picture, or other fixed representation to the eye". Historically, libel has been considered more serious than slander precisely because of its permanence; as one court put it, "The spoken word dissolves, but the written one abides and perpetuates the scandal". Private citizens in every Western democracy enjoy the protection of strong libel laws against harm to their reputation.

"Group libel" extends this idea from an attack on an individual's reputation to an attack on a defined group of people. The stated aim of group libel laws is to protect the basic social standing of individuals against attacks that target them through their membership in a specific group.

However, group libel can become absurd if taken to its logical conclusion. In 1952, the US Supreme Court made a ruling that remains a focal point in the debate over free speech and hate speech. In the case of Beauharnais v. Illinois, the Court upheld the conviction of Joseph Beauharnais, the leader of a white supremacist organization who distributed leaflets in Chicago calling to protect white neighborhoods from the "aggressions...rapes, robberies, knives, guns and marijuana of the negro". The Court treated the Illinois statute under which he was convicted as a "group libel" law, extending the concept of punishable defamation from an attack on an individual to an attack on an entire racial or religious group2.

In a powerful dissent, Justice Hugo Black argued that the entire concept of "group libel" was unconstitutional, asserting that libel law has historically been confined to punishing "false, malicious, scurrilous charges against individuals, not against huge groups". Waldron calls Justice Black’s dissent “perverse,” insisting that libel becomes more serious if applied to a group.

Yet Justice Black’s position reveals a fundamental instability in Waldron's theory. If, as Waldron suggests, a defamatory statement becomes a more serious, criminal matter when applied to a group rather than an individual, the law is immediately plunged into an unworkable calculus of harm.

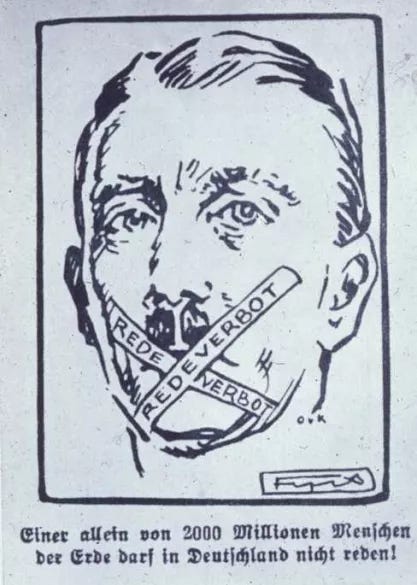

Does the severity of the offense scale with the size of the group? As an uncomfortable thought experiment, is libeling the world’s 2 billion Muslims a crime that is orders of magnitude more severe than libeling the world’s 15 million Jews? Must a court consult census data before passing a sentence? Any legal framework that requires a judge to weigh the 'quantum of harm' based on the population of the targeted group is inherently arbitrary and absurd.

Furthermore, this forces courts into the impossible and dangerous role of social cartographer. What constitutes a legally cognizable 'group'? If one insists that only “minorities” can claim ‘group libel’, then one has to agree on a definition of “minority” as a group with numerical inferiority compared to the “majority”.

By that logic, are 'the wealthy' a group? ‘the ‘top 1%’? 'Police officers'? 'Politicians'? If the theory is to be applied consistently, a court must draw arbitrary lines around which collectives are worthy of protection and which are not. This will create a judicial quagmire, inviting the weaponization of the law by any group that can successfully lobby for protected status.

Justice Black’s dissent was not perverse; it was a prescient warning against a legal theory that, in its attempt to protect everyone in the abstract, ends up protecting no one in particular while creating a system ripe for arbitrary enforcement.

4. The Smallest Minority is the Individual

While Waldron is explicit in framing his argument for 'group libel' as an ultimately individualistic concern, intended to protect the basic social standing of each person within a targeted group, this framing fails to withstand scrutiny. He states: "...though we are talking about group dignity, our point of reference is the individual members of the group, not the dignity of the group as such or the dignity of the culture or social structure that holds the group together". He then continues, "The ultimate concern is what happens to individuals when defamatory imputations are associated with shared characteristics..."

If the harm is truly to specific individuals, as Waldron claims, then traditional libel law (which requires identifying the defamed person) is the appropriate remedy. The very existence of individual libel law renders the concept of a separate 'group libel' doctrinally incoherent within a legal system predicated on individual rights.

A counter-argument is that individual libel law is insufficient: the harm of group libel isn't a particularized injury to one person's reputation but a diffuse, atmospheric harm to the foundational reputation of all members. Even if this is true (and I believe it is), this cannot be the basis of legal intervention because this "atmospheric harm" is legally intangible and non-justiciable. The law requires a victim, and in "group libel," the victim is a statistical abstraction (and, as we have seen, a poorly defined one at that). Hence, ‘group libel’ cannot be a basis of legal theory, especially not in a legal system predicated on the rights of individuals.

The concept of 'group libel' is thus an attempted solution to a problem that arises precisely when no specific individual can claim they have been harmed. It seeks to protect individuals not as individuals, but as undifferentiated members of a collective. In doing so, the theory smuggles a collectivist legal remedy into a system of individual rights, treating the group as the primary entity that has been wronged and its members as mere interchangeable representatives of that collective harm. Therefore, despite his claims to the contrary, Waldron’s 'group libel' is not an extension of individual dignity but a departure from it, requiring the law to see people through the lens of group identity first and as individuals second.

5. The Persistence of Digital Memory

Waldron attempts to narrow the scope of his proposal by focusing on published materials and not fleetingly spoken utterances. He defines these materials as "enduring artifacts of racist expression" that become a "semipermanent part of the visible environment". He argues that the law's primary concern should be the "disfiguring of our social environment by visible, public, and semipermanent announcements". He believes the "sting" of libel is its "permanence of form," because "the spoken word dissolves, but the written one abides and perpetuates the scandal."

First, the very concept of permanence invites reductio ad absurdum. If the goal is to cleanse the 'visible environment' of disfiguring content, must this principle be applied retroactively? Must we take a black highlighter to everything that has ever been published? Must we edit every Teddy Roosevelt biography to expunge his 1886 remarks on Native Americans (“I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every 10 are.”)? Must we, as a matter of legal consistency, also take a chisel to ancient monuments that express hostility towards now-protected groups (for example, an inscription on the Merneptah Stele dated 1208 BC celebrating “Israel is finished”)? The question is facetious, but it exposes the instability of using 'permanence' as a legal standard.

More importantly, the digital age has completely collapsed Waldron’s distinction. If a person utters hateful words with no intent for their preservation, but a third party records and uploads them, making them infinitely and permanently accessible online, who has committed the crime under Waldron’s framework? Is it the speaker, who did not intend to create an 'enduring artifact'? Or is it the uploader, who may have posted the content to condemn it, but is responsible for its permanence? In our brave new world, the distinction between a 'shouted slogan' and a 'tangible feature of the environment' is now meaningless. Any spoken word can become a permanent part of the digital environment in an instant, making a legal theory based on their separation completely unworkable.

6. “Group Libel” leads to Groupthink

Waldron is correct in arguing for the majority Beauharnais v. Illinois opinion that a group-based attack affects an individual's "job and his educational opportunities and the dignity accorded him". It is true that the harm comes from the fact that the individual's "social image and reputation...controls their access to opportunities”. I may even grant him that group reputation decides access to opportunities “more powerfully than…individual abilities ever do". My disagreement is not about the existence of this harm, but about its legal solution.

The reputation of a group, unlike a specific act of discrimination against someone belonging to that group, is a diffuse and social phenomenon. Using a blunt instrument like criminal law to "protect" it is unworkable. The "counterspeech" doctrine, championed by civil libertarians like Nadine Strossen, argues that the only way to genuinely defeat defamatory ideas is to overwhelm them with better ones, thereby truly improving the group's reputation in a way that censorship never can.

Banning "group libel" does little to change the underlying social attitudes that actually limit opportunities. It may even be counterproductive by driving those attitudes underground, where they cannot be openly confronted and refuted. Unchallenged, the suppressed view becomes a shared but tacit common sense. Suppressed, they get tinged with the color of resentment. Even worse, resentment from state censorship often breeds backlash, making martyrs out of hateful bigots.

The Weimar Republic in interwar Germany is the ultimate proof of this phenomenon. It had some of the strongest “hate speech” laws, some of them specifically protecting the Jews. The Republic repeatedly used statutes against incitement and insult to prosecute high-ranking Nazis like Joseph Goebbels and send them to prison. Yet, far from silencing the Nazi movement, the prosecutions provided its leaders with a public platform, generated enormous publicity, and allowed them to masterfully frame themselves as courageous martyrs being persecuted by a corrupt state for daring to speak the 'truth.'

This stark historical example shows how laws against group defamation may have the opposite effect of what Waldron intends them to have. He says: “..I certainly don’t mean that group membership is, in and of itself, a liability. Group defamation sets out to make it a liability, by denigrating group-defining characteristics or associating them with bigoted factual claims that are fundamentally defamatory. A prohibition on group defamation, then, is a way of blocking that enterprise.” Well, it is not.

Waldron's "group libel" approach wrongly targets the expression of an attitude (bigotry), which carries a real possibility of backfiring. A more just and effective legal system targets the discriminatory act itself. The proper legal tools to protect an individual's access to jobs and opportunities are robust anti-discrimination and civil rights laws. If a person is denied a job because of their race or religion, the remedy is to sue the employer for discrimination, not to censor the pamphlets and social-media posts that may have contributed to the employer's prejudice.

7. Make No Law

Waldron's approach is pre-emptive and paternalistic; it seeks to cleanse the informational environment to prevent bad thoughts that might lead to bad actions. The American approach is action-oriented and libertarian; it tolerates bad thoughts and bad speech but ruthlessly punishes the illegal actions that result from them.

Under US law, legal remedies exist for every kind of individual harm that can befall me (discrimination, assault, direct threats of violence) because of an ‘atmosphere’ of anti-Indian hate. And the American approach is the only one compatible with a free society. Because it is the only one that clearly defines the crime and punishes a specific act, rather than attempting the impossible task of policing the human mind through punishing human speech.

There is a growing and dangerous belief that actual physical violence is an acceptable response to 'hate speech.' Hate speech laws just provide an unspoken legal sanction to such views. Such laws signal social endorsement of retaliation. At a minimum, they normalize treating speech as actionable. For example, in Sweden, Salwan Momika, an Iraqi refugee, was murdered while he was being prosecuted by the state for “incitement to racial hatred” for burning a copy of the Quran.

The First Amendment's opening command ('Congress shall make no law') appears absolute. Its strength lies not in a total absence of exceptions, but in the extraordinary difficulty of creating them. Unlike all other democracies, US jurisprudence has evolved in a way that makes it nearly impossible to carve out exceptions based on the content of the speech itself: particularly so for political or social ideas, no matter how offensive. The few narrowly defined categories of unprotected speech, such as incitement or defamation, are grounded in preventing direct, tangible harm, not in policing viewpoints. It is this profound resistance to viewpoint-based regulation that makes the American approach exceptional.

In the upcoming second part, I will demonstrate that Waldron's distinction between protecting dignity and preventing offense, while philosophically coherent, is practically irrelevant. The troubled outcomes from hate speech legislation in other democracies make the wisdom of the US First Amendment’s high barrier even more clear. It is these troubled outcomes that we will examine in the next part.

With thanks to Mike Riggs for edits. And to Rishi Pethe, Colleen Smith, and Afra Wang for feedback during the drafting process.

I drafted this essay before Kirk’s tragic, senseless murder, and did consider excising the reference to his tweet. There’s precious little I agreed with him on, and definitely not on his views on Indian immigration. But, watching clips of his debates, he comes across as someone who believed in dialogue and letting his opponents speak (which is more than he was, ultimately, allowed). So I have decided to keep his words in the essay. His words are all we have of him now. This essay is dedicated to Charlie Kirk.

Many First Amendment scholars are of the view that the 1964 New York Times Co. v. Sullivan judgment has effectively overturned the 1952 Beauharnais v. Illinois judgment. Waldron disagrees, saying that the “public figure doctrine” used in Sullivan may not apply to Beauharnais.

I’m looking forward to part 2. Great essay!

This is a really astute analysis of a complex issue.

One takeaway I can mention, among many, is that what often at the surface might seem like a good thing can actually end up being not only counterproductive but often dangerous. This for me is humbling to read, and should be sobering for people who are keen for regulatory interventions on the basis of strong personal emotions or experiences however unfortunate.

I commend the comprehensive nature of your treatment of this subject, Venky, in particular how you dissect the problem from the proposed solution, how you are taking an intellectual approach (appreciate people on all sides for arguments you think are valid) rather than a political one (taking sides).

Good intentions are never proof or a guarantee of good outcomes, but it's so easy, in the heat of the matter, to forget this. Look forward to the next part.